Mary Anning

Lived 1799 – 1847.

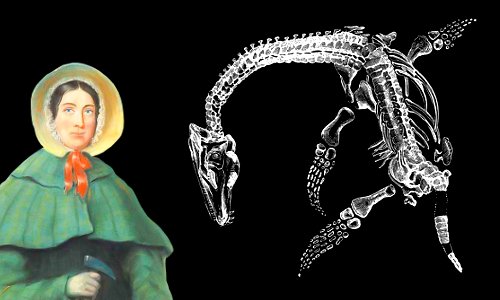

Mary Anning was born into poverty, but became the greatest fossil finder of her era, powerfully influencing the new science of paleontology. She overcame a lack of formal education to emerge as one of the foremost authorities on fossils.

A specimen she discovered jointly with her brother provided the data for the first ever scientific paper about the ichthyosaur. She discovered and drew the first ever complete specimen of a plesiosaur; her discovery of fossilized feces allowed ancient animal diets to be deduced; and she discovered a fossil fish that bridged sharks and rays. All of this was achieved before her thirtieth birthday.

Her advice guided the work of many of highest-ranking geologists and paleontologists of her day. Her discoveries formed the basis of the earliest popular portrayal of prehistoric species.

Beginnings

Mary Anning was born on May 21, 1799 in the small resort town of Lyme Regis, England, UK.

Her father was Richard Anning, a carpenter and cabinetmaker. Her mother was Mary Moore. The couple had 10 children, of whom only two survived childhood – Mary and her older brother Joseph.

Mary’s own survival was said by her parents to be a miracle. At the age of 15 months old, Mary was being cared for by one of her parents’ friends at a horseshow. A sudden rainstorm made people run for shelter. Mary, her babysitter, and two children took shelter under an elm tree. A lightning strike killed them all except Mary. Before the lightning strike Mary had been a sickly child; after the strike she enjoyed robust health.

As Mary grew up, her parents credited the lightning strike with her high intelligence, boundless energy, and gritty determination.

Sunday School

Mary’s parents belonged to a Congregational church that believed in educating everyone. Starting at about age eight, Mary was taught to read and write at Sunday school.

Fossils

Mary’s father’s carpentry business did not make much money. The home he and his family rented was close to the sea, so close that it sometimes flooded during storms. The storms, however, were not entirely bad news – they were actually a source of extra income.

The small town of Lyme Regis sits on what is now called the Jurassic Coast. The coastline is gradually being eroded by the sea, and storms regularly cause sections of the coast’s cliffs to collapse, releasing fossils from rocks laid down about 200 million years ago during the Jurassic era.

Rock layers on the Jurassic Coast

Rock layers on the Jurassic Coast

By the early 1800s, Lyme Regis had become a resort town, visited by wealthy people who were happy to buy souvenirs. Mary’s father collected fossils liberated by storms and sold them to tourists.

A Jurassic Coast ammonite

Jurassic Coast fossils in rock

Mary and her brother Joseph often went to the base of the local cliffs to help their father search for fossils.

Layers of rock in the cliffs at Lyme Regis. Image by Michael Maggs.

Fighting Against Poverty

In November 1810, when Mary was aged 11 and Joseph 14, their father died of tuberculosis. He died in debt, so the family faced not only losing its breadwinner, but the further hardship of paying down debt while trying to make enough money to live on.

Between 1811 and 1816, the family received assistance from the Overseers of the Poor; this usually took the form of a little money, food, or clothes. The Annings were not alone in needing financial help; this was a hungry time for many British people. Food had become unusually expensive because of Napoleon Bonaparte’s wars to conquer Europe. Moreover, Britain and much of Europe and North America were suffering their coldest decade for over a hundred years, reducing crop yields – the cold weather was caused by volcanic eruptions in the tropics in 1809 and, especially, the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 – the largest eruption in recorded history.

The Anning family had no skills, except for fossil-finding skills Mary and Joseph had picked up from their father. They lived hand-to-mouth, finding small fossils underneath the cliffs, while their mother ran a small stall selling the fossils to wealthy tourists.

A Momentous Discovery Helps

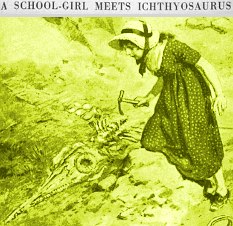

Near the end of 1811, Joseph found an ichthyosaur skull. A few months later, Mary, who was just 12 years old, found the rest of the skeleton.

Joseph and Mary discovered the most complete example of an ichthyosaur found at that time. Their find was Temnodontosaurus platyodon, shown above with an adult human for comparison of relative sizes.

Joseph and Mary’s discovery was used as the basis for the first ever scientific paper written about the ichthyosaur, published in 1814 by Everard Home.

The young fossil finders received no acknowledgement in Everard Home’s paper. Science was an activity for gentlemen, but Joseph, Mary, and their mother were lower-class commercial dealers. The gentlemen of science believed the only acknowledgement the Annings were due was payment. Most of Mary’s later discoveries described in scientific papers were not credited to her either.

By 1819, the ichthyosaur discovered by Joseph and Mary was on display at the British Museum in London.

Saved from Hunger

Joseph began an apprenticeship with an upholsterer in about 1816. Mary then began taking a more prominent role in the business. It was a precarious existence. If finds dried up for a few months, the family went hungry.

By 1820, Mary had found nothing of any significance for almost a year. The family started selling their furniture to pay the rent. A local naturalist by the name of Thomas Birch was appalled; he decided to help the Annings.

Birch had an excellent collection of fossils; the Annings had sold him most of his best specimens. He auctioned these in London, where he knew he would get top prices. He used the money to make the Anning family’s finances secure. Lyme Regis’s scandalmongers said he did this because he was attracted to Mary, who was now 21 years old, but there is no evidence for this; it was probably a straightforward act of generosity.

Dangerous Work

Finding the best fossils on the Jurassic Coast was dangerous work. Mary needed to search among rocks that had just fallen from the cliffs. One rockfall was often followed quickly by another.

Mary’s pet dog was killed by falling rocks, and she herself had a number of narrow escapes from serious injury or death. Nevertheless, she kept going; she was both physically and mentally very strong. She wrote to a friend:

“Perhaps you will laugh when I say that the death of my old faithful dog quite upset me, the cliff fell upon him and killed him in a moment before my eyes, and close to my feet, it was but a moment between me and the same fate.”

“Perhaps you will laugh when I say that the death of my old faithful dog quite upset me, the cliff fell upon him and killed him in a moment before my eyes, and close to my feet, it was but a moment between me and the same fate.”

MARY ANNING

Mary Anning’s Discoveries

The Knowledge and Skills

In addition to searching for fossils, Mary Anning began to take a more scientific approach to her work, finding out about anatomy and reading scientific papers. The language used in these papers was difficult for a young woman with little education to understand. However, she studied scientific works with great diligence and learned the scientific jargon. She went as far as learning French so she could read works by Georges Cuvier, the eminent naturalist and paleontologist.

She also learned how naturalists made deductions from their observations, how museums prepared specimens for display, and she became an expert in the delicate work of removing fossilized bones from rock, then reconstructing skeletons.

The Birth of Paleontology

In 1821, things began to look up. Anning found three fossilized ichthyosaur skeletons, ranging from 5 to 20 feet long. She was now working at the forefront of a new science utilizing fossils to reveal Earth’s natural history. In 1822, Henri de Blainville gave this new field a name: paleontology.

The artist and fossil collector George Cumberland described Mary’s 5 foot ichthyosaur in January 1823:

“the very finest specimen of a fossil Ichthyosaurus ever found in Europe… we owe entirely to the persevering industry of a young female fossilist, of the name of Anning… and her dangerous employment. To her exertions we owe nearly all the fine specimens of Ichthyosauri of the great collections…”

“the very finest specimen of a fossil Ichthyosaurus ever found in Europe… we owe entirely to the persevering industry of a young female fossilist, of the name of Anning… and her dangerous employment. To her exertions we owe nearly all the fine specimens of Ichthyosauri of the great collections…”

GEORGE CUMBERLAND

Bristol Mirror, January 1823

Plesiosaurus

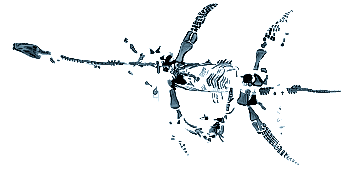

In December 1823, aged 24, Anning made the first ever discovery of a complete Plesiosaurus skeleton.

This was a truly amazing discovery – so striking that many scientists refused to believe such a creature had ever existed. Georges Cuvier, whose works Anning had learned French to study, declared it to be a fake. The head was much too tiny ever to have belonged to the body, he said.

Mary Anning’s own drawing of the complete Plesiosaurus fossil she discovered.

After Cuvier had examined the fossilized creature, he declared:

“It is the most amazing creature ever discovered.”

“It is the most amazing creature ever discovered.”

GEORGES CUVIER

Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles, 1824

The discovery of Plesiosaurus made Anning’s name. People came from far and wide to Lyme Regis, eager to meet her. One wealthy visitor, Lady Harriet Silvester, wrote in the fall of 1824:

“she has made herself so thoroughly acquainted with the science that the moment she finds any bones she knows to what tribe they belong. She fixes the bones on a frame with cement and then makes drawings and has them engraved… by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.”

“she has made herself so thoroughly acquainted with the science that the moment she finds any bones she knows to what tribe they belong. She fixes the bones on a frame with cement and then makes drawings and has them engraved… by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.”

LADY HARRIET SILVESTER

Diary Entry, September 1824

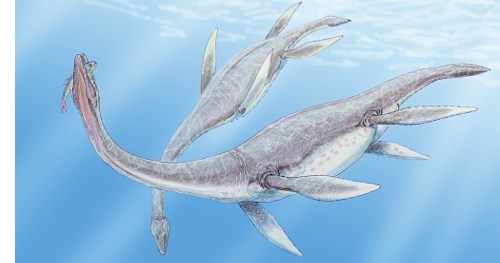

Modern depiction of Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus by Dmitry Bogdanov.

1828 – A Good Year for Discoveries

In 1828, Anning made a series of big discoveries.

Inkbag

First there was the ink bag of Belemnoidea fossils. Belemnoidea were 10-armed creatures that could eject ink into the water, similar to modern squid or cuttlefish. The fact that they possessed ink bags and were capable of squirting ink was discovered by Anning.

Remarkably, Anning found that the ink in the bags had survived fossilization and could still be used in pens. This boosted visitor numbers to Lyme Regis, with people turning up to see this ancient natural wonder. Artists in the town began using Belemnoidea ink to draw pictures of fossils found in the area.

Fossilized Poop

Anning found examples of fossilized animal feces in 1824, although she was unsure of what she had found.

In 1828, she found more of these objects in the abdomens of ichthyosaurs. Breaking some open, she found bones and fish scales. She deduced she was handling fossilized feces. Studying the contents of fossilized feces has given scientists a window on the diets of animals hundreds of millions of years ago.

A sample of fossilized dinosaur feces.

Flying Reptile

Anning’s next discovery further boosted her fame, and brought even more visitors to see her in Lyme Regis.

Modern depiction of Dimorphodon macronyxby Dmitry Bogdanov.

Her find was the first ever discovery of the Dimorphodon genus.

The species she discovered was Dimorphodon macronyx, shown in the image.

1829 – Major Discoveries Continue

An Even Better Plesiosaur

Anning found a second plesiosaur fossil in 1829, even more complete than her pivotal discovery of 1823.

Squaloraja – A Fossil Fish

The discovery of Squaloraja – an extinct fish that seemed to be part shark, part ray proved very interesting. Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace’s theory of evolution by natural selection lay almost 30 years in the future and scientists were still trying to make sense of what fossils were telling them about natural history.

1830 – Plesiosaurus Macrocephalus

In 1830, Anning discovered one of her most complete and beautiful fossilized creatures – Plesiosaurus macrocephalus. A cast of this fossil is on display at the Natural History Museum in Paris, France.

Plesiosaurus macrocephalus. Image by FunkMonk.

1830 – Duria Antiquior Hints at Evolution

In 1830, the geologist Henry De la Beche painted the first popular portrayal of prehistoric life, basing it on Anning’s discoveries. The profits from prints of the picture were donated to the Annings. De la Beche’s painting caught the public imagination, allowing ordinary people to picture what life looked like in the distant past.

The painting showed a world whose animals were very different to the familiar animals of the modern world; it encouraged more people than ever before to speculate about processes that could cause species that once populated Earth to disappear and be replaced by new species.

The above water scene in Duria Antiquior.

The underwater scene in Duria Antiquior.

How old is the Earth?

Anning was a devoted Christian. She lived in a time when many people believed James Ussher’s literal interpretation of the Bible, from which he deduced Earth was made in 4004 BC. Many people also believed that everything in the universe had been made within a week.

In 1833, Anning told the Reverend Henry Rawlins and his son Frank that the fossils she had found in different layers showed that the animals had been created and had existed during different eras. Later, a disapproving Reverend Rawlins refused to discuss the issue further with Frank.

Her upbringing in a dissenting church possibly helped Anning take a flexible view of Earth’s history.

Although she did not believe Ussher’s literal interpretation of the Bible, Anning remained committed to the church all her life – first the Congregational church, then the Church of England – she donated money to both. The book she read most frequently was the Bible.

Some Personal Details and the End

Anning never married and had no children. Her life was a hard one.

In 1815, when she was 14 and looking for fossils on the beach, she found the body of a young woman, one of over 100 people who had died when the ship they were sailing in sank. The body was taken to the church. Anning’s discovery affected her deeply; she visited the church every day, placing a fresh layer of flowers on the body at every visit until relatives claimed it.

In 1837, the German naturalist and explorer Ludwig Leichhardt met Anning and recorded his thoughts:

“We had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of paleontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression. Every morning, and after every stormy sea, she goes walking and clambering about on the slopes of the Lias to see whether fossils have been brought to light by falls of rock or wave action.

“We had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of paleontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression. Every morning, and after every stormy sea, she goes walking and clambering about on the slopes of the Lias to see whether fossils have been brought to light by falls of rock or wave action.

LUDWIG LEICHHARDT

1837

Leichhardt was wrong about Anning’s age by a decade. She was actually 38 when he visited her.

A year later, the British Association for the Advancement of Science began paying Anning a small income from an annuity. Although she was a commercial fossil dealer who had never published any scientific papers, her work had been of such crucial importance that the Association felt it was appropriate to provide her with an income.

Despite her discoveries and her fame, however, Anning remained poor. A wealthy friend, Anna Maria Pinney, who sometimes searched for fossils with her under the cliffs, wrote:

“she is very kind and good to all her own relations, and what money she gets by collecting fossils, goes to them or to anyone else that wants it.”

Anna Maria Pinney also wrote about her friend’s frustration that her contributions to science had not been fully credited:

“She says the world has used her ill and she does not care for it, according to her account these men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal by publishing works of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages.”

In the last few years of her life, Anning became increasingly sick, suffering from breast cancer, which was diagnosed in 1845. When the Geological Society’s members learned of her plight, they started a fund that paid for her treatment.

Anning was given an opiate based drug, laudanum, as a pain-killer. Characteristically, she refused to complain about her illness, so the townspeople of Lyme Regis mistook the effects of the drug for drunkenness. They did not realize that Anning was desperately ill.

Mary Anning died, aged 47, of breast cancer in Lyme Regis on March 9, 1847. She was buried in the churchyard of Lyme Regis Parish Church. Three years later, the Geological Society paid for a large stained glass window dedicated to her, portraying religious acts of charity, to be placed in the church.

Mary Anning’s name was never forgotten. She was seen as a trailblazer for girls and people of humble origins who wished to become scientists.

Mary Anning depicted in a children’s encyclopedia in 1925.

During Anning’s lifetime, the Swiss paleontologist Louis Agassiz named two species of fish in her honor: Acrodus anningiae in 1841, and Belenostomus anningiae in 1844. In doing so, he acknowledged his thanks for help she gave him when he visited Lyme Regis in 1834.

Later namings for Anning have been: the therapsid reptile genus Anningia, the bivalve mollusc genus Anningella, the plesiosaur genus Anningasaura, and the Ichthyosaurus anningae species.

In 2010, the Royal Society recognized Mary Anning as one of the ten British women who have most influenced the development of science.

No comments:

Post a Comment