Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Early Life and Education

Santiago Ramón y Cajal was born in Petilla de Aragón in northern Spain on May 1, 1852. His mother’s name was Antonia Cajal. His father, Justo Ramón Casasús, was a surgeon and Professor of Applied Anatomy.Ramón y Cajal was a mischievous boy, often in trouble at school. He attended several schools, as his family tried to find one he would settle down in and behave properly.

He was very good at drawing, but he did not enjoy the strict and sometimes violent discipline of the monks who taught at his schools.

His father lost patience with the boy and withdrew him from school, apprenticing him to a barber, which did not work out well, and then a cobbler, which also did not work out well. Ramón y Cajal wanted to be an artist and he was very strong-willed. He returned to high school in the town of Huesca.

In the summer of 1868, his anatomist father took the 16 year-old boy to graveyards where the bones of ancient burials had come to the surface. His father hoped that by interesting his son in drawing the bones, he would excite his interest in anatomy.

His father’s ploy worked, because in 1868 Ramón y Cajal enrolled to study medicine at the University of Zaragoza, where his father was a professor.

He performed well at university, under his father’s guidance, and became very skilled at dissection. In fact, he became so good that three years into his course he was employed as a dissection teaching assistant. He also won a prize for top student.

In 1873, after five years at medical school, Ramón y Cajal graduated. He was now qualified to practice medicine. He was just 21.

Soon he was conscripted into the army.

Advertisements

The Army

After a few months in the army Ramón y Cajal applied successfully for the Medical Corps, which had many more applicants than positions.In 1874, his army unit moved to the Spanish colony of Cuba, where the Ten Years’ War of independence had been fought since 1868. The following year he was posted back to Spain from the tropical nightmare of Cuba. He was suffering from dysentery and malaria. The malaria almost killed him.

Out of the army, he spent time in the care of his mother and sisters in the foothills of the Pyrenees Mountains in northern Spain.

Scientific Career

In late 1875, Ramón y Cajal started as a graduate assistant at the University of Zaragoza. In early 1877, he was promoted to acting assistant professor and awarded a Ph.D. degree in medicine.In 1879, he became the Director of the Anatomical Museum in the University of Zaragoza’s Faculty of Medicine.

In 1883, he moved to become Professor of Descriptive Anatomy in the University of Valencia’s Faculty of Medicine.

In this early part of his career, he worked on the causes of inflammation, cholera, and the structure of epithelial material.

In 1887, he took the chair of Histology and Pathological Anatomy at the University of Barcelona. It was here he began to make serious use of Golgi’s Method, which would ultimately lead to his Nobel Prize.

In 1892, he became Professor of Anatomy and Histology in the Pathological School of Medicine at the Central University of Madrid. He stayed in this position for thirty years, until he retired in 1922.

Nobel Prize Winning Scientific Research

Golgi’s Method and Nerve Cells / Neurons

In 1873, Camillo Golgi discovered that silver nitrate and potassium dichromate together fixed particles of silver chromate to the membranes of nerve cells. This resulted in the nerve cells becoming visible on a yellow background. (Nerve cells are also known as neurons.)Nerve cells are extremely important, because they carry information through the body using chemical and electrical signals. Nerve cells carry information to the brain from, for example, our senses such as sight and hearing. Nerve cells also carry the brain’s response back to the body causing, for example, muscle movements.

Understanding the nervous system is vital to our ability to understand the biology of higher living organisms, including humans.

Golgi’s method of staining neurons allowed them to be seen with great clarity for the first time. It was not perfect, however, because fewer than five percent of neurons took up the stain.

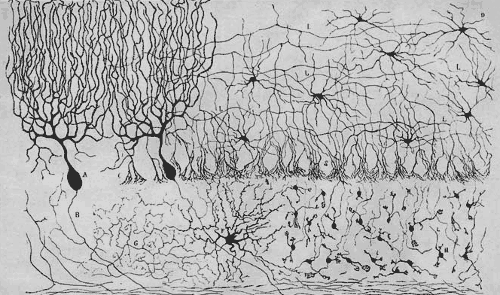

In 1887, Ramón y Cajal began using Golgi’s method to study neurons. He improved the method by using higher concentrations of the chemicals, cutting thicker sections of material to study under the microscope, and only using the method to study those neurons that it performed best on. These were neurons with unmyelinated axons. This meant that the axons – these are the structures that carry nerve signals – were not surrounded by fat. Bird brains and mammal embryos contain unmyelinated axons, so were ideal for Ramón y Cajal’s work.

He found he could stain a much greater proportion of neurons than Golgi could.

Ramón y Cajal’s drawing of the neurons in a bird’s cerebellum – a part of the brain.

The Neuron Doctrine

Within a year Ramón y Cajal published a groundbreaking result. He discovered that the nervous system in bird brains is made up of individual cells touching one another – he could show this clearly, because of the high proportion of cells he was able to stain.This discovery, in 1888, made it the peak year of his work, according to Ramón y Cajal.

It allowed him to establish proof of the neuron doctrine, which is now the absolute basis of neuroscience.

The neuron doctrine states that neurons are individual, separate cells. They behave as biochemically distinct cells rather than a network of interlinked cells.

Golgi, who invented the stain, disagreed strongly with the neuron doctrine. He maintained that neurons formed an interlinked network which behaved as a single entity. In fact, this was the position of most scientists until Ramón y Cajal established his neuron doctrine.

Rivals Share the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prize committee decided that Ramón y Cajal and Golgi should share the 1906 Nobel Prize for Medicine/Physiology, even though the two scientists held absolutely opposite views about how the nervous system worked. If one of them was right, the other one must certainly be wrong.Ramón y Cajal had much better evidence for his position.

It’s likely that Golgi’s prize was for the discovery of the basic technique that allowed Ramón y Cajal to prove the neuron doctrine.

As regards sharing the Nobel Prize with his rival, awarded “in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system,” Ramón y Cajal said:

What a cruel irony of fate, to pair together, like Siamese twins united by the shoulders, scientific adversaries of such contrasting character!

What a cruel irony of fate, to pair together, like Siamese twins united by the shoulders, scientific adversaries of such contrasting character!

Santiago Ramón y Cajal

The other half was very rightly awarded to the illustrious professor of Pavia, Camillo Golgi, the inventor of the method with which I accomplished my most striking discoveries.

The other half was very rightly awarded to the illustrious professor of Pavia, Camillo Golgi, the inventor of the method with which I accomplished my most striking discoveries.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Photography

Ramón y Cajal was an enthusiastic photographer.When he first took up photography, people had to pose for several minutes while the photographic plate gathered enough light to produce a picture.

Ramón y Cajal invented a new process in which only three seconds worth of light was needed to produce a photograph. Unfortunately, he learned Thomas Edison had beaten him to it.

As a result of his enthusiasm for photography, more photographs of Ramón y Cajal exist than for most scientists of his era.

For example:

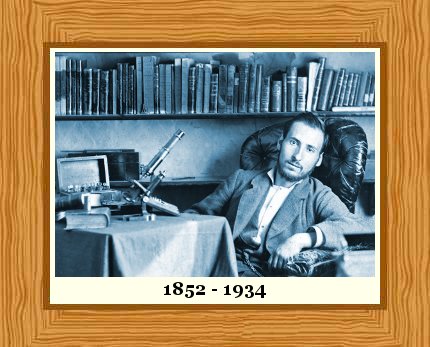

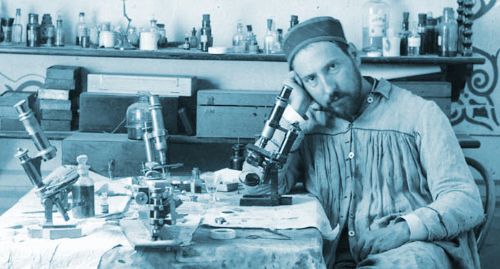

Santiago Ramón y Cajal in the mid-1880s in his laboratory with his favorite tool – his microscope. Perhaps photographed at the end of a hard day?

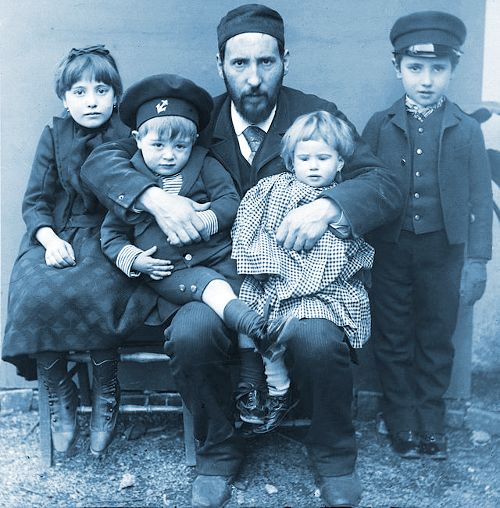

Santiago Ramón y Cajal with his children Fe, Santiago, Jorge and Paula in 1889.

The End

Santiago Ramón y Cajal died at the age of 82, on October 17, 1934. The death of his wife, Doña Silvería Fañanás García, in 1930 had been a blow to his morale. The couple are buried together in Madrid. They were survived by four daughters and two sons.

No comments:

Post a Comment